„2 turntables, a mixer, my universe“Interview: Andy Rigby-Jones on designing the DJ mixers MODEL 1 & MODEL 1.4 for Richie Hawtin

4.3.2021 • Technik & Wissen – Interview: Thaddeus Herrmann

Andy Rigby-Jones and Richie Hawtin

The history of DJing has many facets. Of course, it is primarily about music, but also about skills. Thus, the further development of DJing is also always a piece of technical history. From turntables and record needles to the heart of every set-up: the mixer. What used to be just for two turntables is now often a sound card, MIDI controller, effects unit and interface to the laptop all in one. We talked to Andy Rigby-Jones. He was responsible for the design of DJ mixers at Allen & Heath for many years and made (digital) history during this time. Together with and for Rich Hawtin, he also developed the two PLAYdifferently mixers MODEL 1 and the brand new MODEL 1.4.

In 2016, a jolt went through the DJ community. Once again. Since Final Scratch, Serato, Traktor, the triumph of CDJs and ever more sophisticated technology, the job title "DJ" no longer stood for the type of person who roamed the country with heavy metal suitcases filled to the brim with 12"s. Records were more and more on the way out, replaced by digital possibilities. Richie Hawtin has been an evangelist of this digital change from the very beginning, neither wanting to carry on lugging nor limiting himself to records for his gigs. Samples, loops, many more sound sources: The laptop promised exactly the same revolution for DJs that it had brought about a few years earlier in studios and on stages.

So in 2016, Hawtin introduced his first "own" DJ mixer: MODEL 1. A beast of a machine, incorporating the results of many years of experience with hybrid setups. The goal: to equip the digital reality of the gig between Traktor and CDJs with analogue warmth on the one hand, and to create as open a system as possible that would meet all requirements on the other. The features were and are endless – and cost over 3,000 €. For a 6-channel mixer nowadays maybe ok, but then only something for those for whom two Technics or two CDJs are not enough. For those who have long since understood the DJ gig as a performance, where their own creativity has long since meant more than that of the track producers. Recently, the second mixer in the series was released: MODEL 1.4, with only four channels instead of six, but the same analogue design – and it sells for about 1,000 € less. Hawtin says this is best suited for smaller studios and perfect for streaming.

Both mixers were designed by Andy Rigby-Jones. He's a legend in the mixer business. He not only shaped the Allen & Heath DJ portfolio, but made it possible in the first place. So instead of talking to the DJ, we talked to the engineer.

About Andy RigbyJones

Andy Rigby-Jones grew up on a farm in Cornwall and founded an agricultural machinery business with his father in 1982. In 1992, he started working with Allen & Heath, the company was located around the corner. As an electronics and audio nerd, he worked his way up there and stayed for some 22 years. In 1994, he became part of the research department. During his time there, he worked on the live mixers of the MixWizard, GL and ML series, among others. On the side, he was always DJing. It has been his hobby since the 1970s. His passion for DJing finally made him the key figure at A&H from 1999 onwards for the development of the Xone mixers, which were specially designed for DJs. In 2014, he set up his own business and founded Union Audio Limited. The first product was the MODEL 1, which was created in collaboration with Richie Hawtin. In addition to the design of the new MODEL 1.4, Andy Rigby-Jones has been primarily responsible for new products from MasterSounds – a brand of Ryan Shaw – in recent years. Union Audio Limited not only designed numerous rotary mixers for him, but also manufactured them.

Let’s break the rules a little bit and start with a story from the interviewer. I bought my first (and to this day only) DJ-mixer in the late 1990s: a Pioneer DJM-500, alongside with my second MK2. It is still working to this day, although the faders could need a bit of a cleaning. My point is: It still does what I am looking for in a DJ-mixer: Looking back at the last 25 years ... what did I miss? At which point did the mixer turn into musical instrument and why? Given your history as someone who’s been DJing since the 70s, I’m sure you have a comment.

I think it’s great that your DJM500 still works and gives you enjoyment. It was an innovative product for the time, and given it’s lasted 25 years, was clearly well made. Super cheap, poor quality DJ kit is morally wrong in my opinion, these products often don’t perform well when new, and have a limited lifespan before being thrown away. The cost to the environment is simply not reflected in the price. But getting back to your question, the last 25 years have seen a huge change in DJ technology. However, it's interesting to note that the tactile element has remained. Ten or fifteen years ago, some were convinced that touchscreens were the future. But from my own experience I never felt that was going to happen. You need the physical feedback that only hardware can provide, whether it is a turning a knob on a mixer or hitting a play button on a CDJ.

In the early 2000s, laptops emerged. My first brush with this technology came when Richie Hawtin sent his A&H Xone:62 in for a service. We looked at it in some bemusement as it was covered in MIDI controls that his dad had added. I remember thinking "what’s this all about"! A couple of years later I saw some DJs playing with a Hercules DJ Console in the lobby of a hotel during the Winter Music Conference. It looked like a toy, but the potential was obvious. That year, at the Frankfurt Music Messe, I also watched Richard Devine playing a DJ set with Traktor, using an ordinary MIDI keyboard. It was quite inspiring, and I set about designing the Xone:3D as soon as I got back to the office.

For a few years it seemed like almost every DJ had a laptop in the booth, then Pioneer did something very clever, they put the laptop inside a CDJ. Suddenly DJs had all the power of software but without having to carry a load of hardware around. And better still, they could enjoy the classic two-deck-with-a-mixer-in-the-middle layout that just seems so natural. I think this has possibly been one of the biggest innovations in recent times, though it seems a bit like cheating, turning up to a gig with nothing more than a memory stick…

As to which point did the mixer turn into a musical instrument, I think Grand Wizard Theodore made that change back in the 70s!

You started working on a dedicated DJ-mixer for A&H in the 90s, a modified MixWizard, as a personal project. What did you envision at the time? How did you want to improve the concept of the DJ-mixer back then?

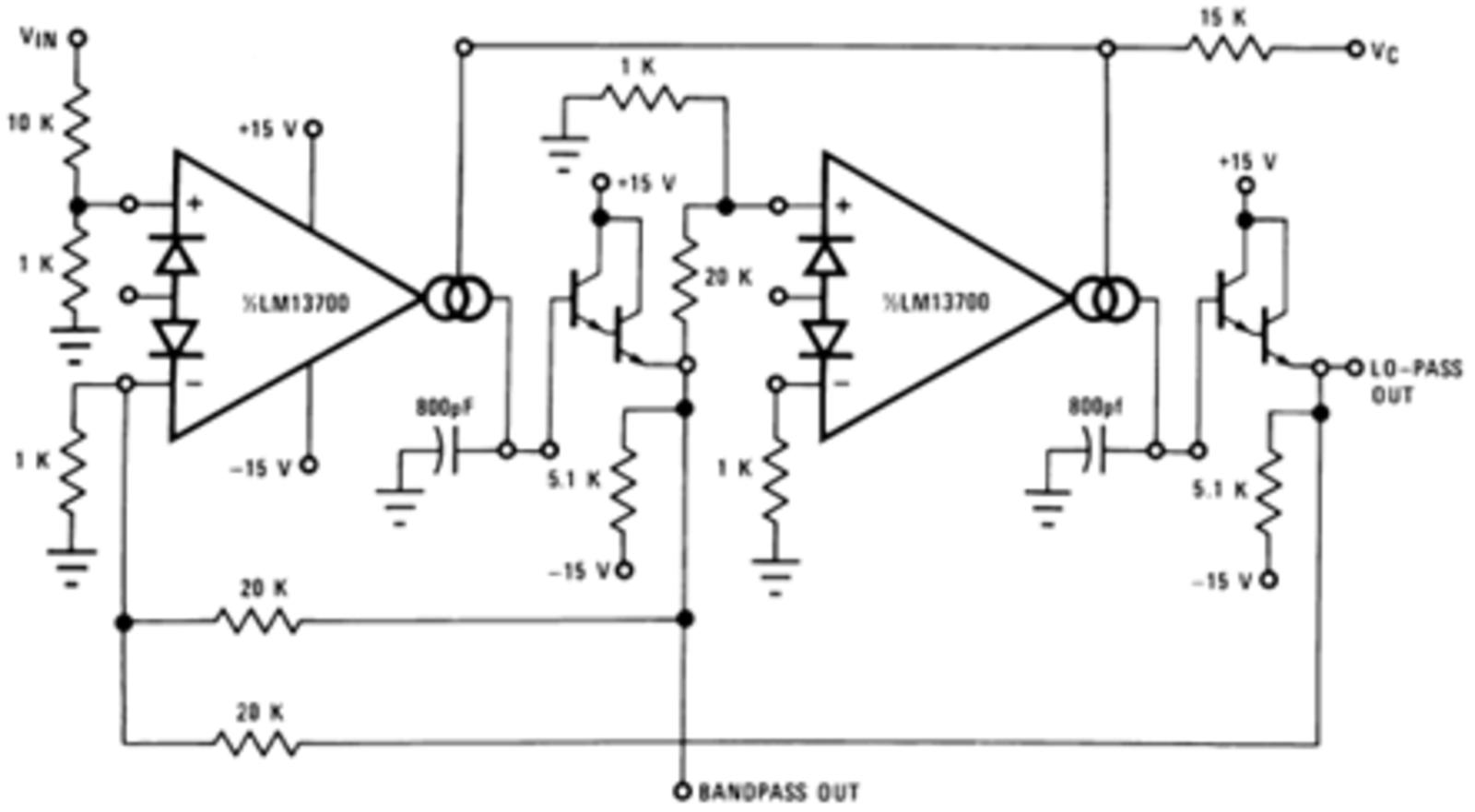

The desire to actually design a DJ mixer was inspired by playing with a voltage control filter circuit that I found in the Texas Instruments data sheet for the LM13700 transconductance op-amp – it’s still in print, and this is the circuit …

I think it’s now probably safe to admit that I wasn’t actually supposed to be playing with a filter circuit as I had been tasked with developing a low-cost voltage control amplifier. But the filter circuit looked too interesting not to breadboard and no one seemed to notice – well if they did, they never mentioned it … I was so intrigued by the sound of that filter I immediately wanted a DJ mixer with it incorporated, if only for my own use. Which is why in the latter half of 1998 I asked the management to allow me to design a DJ variant of the MixWizard. Besides a filter I also wanted a better EQ, as nearly all mixers then had symmetrical cut and boost, with too much boost, and not enough cut. As the A&H Live sound consoles had four-band EQ, it seemed natural to add this to a DJ mixer.

Can you elaborate on the challenges?

The biggest challenge was convincing senior management to fund the development of the prototype into a commercial product, as back then A&H were part of the Harman Group, and finances were strictly controlled. After some initial reluctance they agreed, on the proviso that the DJ mixer design used components already stocked. The next challenge was to persuade the distribution network to take on a DJ line – most distributors came from a rock'n'roll or Live sound background, and "DJ" was a dirty word! Then it was all about winning DJs over to the new brand, and some features of the mixer, such as the four-band EQ, were not instantly liked.

Over the course of the couple of last decades, the DJ-mixer turned from a commodity into a highly sophisticated piece of equipment. Was there a tipping point in this development from your perspective?

Software DJing had to be the tipping point. When you have the ability to run multiple synchronised sources, you are going to require lots of channels to mix them down.

When laptops became a given with DJing, what did you personally think of this development?

I converted from a sceptic to an evangelist in the space of about three months. At first, I just thought it was a gimmick, but as soon as I understood the power that software replay and manipulation offered, I was sold. Ableton Live was what first exposed me to computer DJing, but it was Traktor that really made it work for most DJs. One thing I did find fascinating was how readily the technology was accepted. Back when I was DJing there was a big backlash against CDs, i.e. if you weren’t spinning vinyl you weren’t a proper DJ, yet this never really happened to the same extent with laptops.

Developing a DJ-mixer today involves bringing together a lot of different expectations and technical standards. From the analogue beginnings, embracing the up and coming digital realm to finally combining the best of both worlds, delivering a hybrid solution: What does a DJ-mixer has to offer in 2021, marrying digital openness and analog robustness?

When you think about it, the basics of a DJ mixer haven’t changed much in my lifetime – you still need input and output level controls, some kind of signal level monitoring and a cue system. All the cool features like Filters, hybrid EQs etc are optional. There are currently mixers available that cover a very broad range, from the simplest two-channel vinyl mixer all the way up to a DJ production tool, like the MODEL 1. From a DJ perspective it’s all about choosing the features that fit with the way you want to play or create music. And from a design perspective, it’s about adding the features needed for the market segment you are targeting.

MODEL 1.4

Technology is still moving fast. Can you identify standards which are here to stay, kind of volatile trends you’d currently rather not implement in future products and visionary ideas that still need to be invented?

Technology does move fast, but what I have found fascinating in recent years is watching the resurgence in vinyl; who could have predicted that? Certainly not Technics who discontinued the SL1200 years ago, only to have to relaunch it recently! So, I think RIAA inputs are here to stay for a while longer, as well as the ubiquitous Line input. S/PDIF interconnects also, though they might possibly give way to a newer format as sample speeds and bit depth increase. I’m not convinced that internal USB soundcards are the future due to the benefits of the latest generation of standalone players, which make them redundant. And I can’t imagine designing a mixer with a Bluetooth interface either.

How did you first meet Richie? When did you decide to work together?

I met Rich in 1999 at 107th AES in New York. It was my first trip to the USA, and I was on the booth demo’ing the new prototype Xone mixers, when both he and, I think also Jeff Mills, walked up – I remember I was a bit star struck! After that meeting, Rich kept in touch and we developed a great working relationship, his input being very valuable on the Xone:92. We also made a super limited edition (a total of five) CTRL:92s for him to use. By the end of 2013 I told him I was planning to leave A&H to start my own company, and in 2014 we got in touch again and started bouncing some ideas back and forth, which ultimately led to MODEL 1.

MODEL 1 was (and is) an impressive piece of engineering. Is it the way to go forward for the mass market, too?

MODEL 1 is a DJ production/Live remix tool, a fairly niche market, so I don’t think it’s ever going to appeal to everyone. It’s also prohibitively expensive for many DJs.

I’m asking because at Union Audio Ltd, you offer services on an OEM-level as well, coming up with designs and ideas, tailored to the client’s requests. From cheap USB-interface-possibilities to high-end rotary faders and discreet analoge designs, where do you see the industry going in the near future?

When I started Union Audio, I expected the design work to dominate, with small run, batch manufacturing, as a side-line. What has taken me by surprise has been the success and growth of the MasterSounds brand, which has been nothing short of phenomenal. So much so, that the focus of the company has shifted towards manufacturing, leaving me with little or no time to concentrate on the design side. Add to this the COVID situation, making it almost impossible to recruit new staff, and the last year has been pretty crazy from a work perspective. Hopefully, once things start returning to normal we can increase the workforce and I can get back to designing again.

With more technical possibilities comes a steeper learning curve. Spinning music – for the most part – has always been about artistic freedom. 2 turntables, a mixer = my universe. Once DJing got more and more digital, it also got more complicated. And more expansive. How do you assess this trend?

As previously mentioned, the recent resurgence in vinyl is interesting. I feel it’s almost a reaction to the technology which has been dominating the booth for the last fifteen years or so. And of course, there’s a whole new generation of DJs that never previously experienced mixing on vinyl, so to them it’s a new experience. And you are right, there is something very organic about mixing vinyl. It’s hands on and tactile (that word again), and you can see the technology in action as the needle follows the groove in a spinning disc. On the other hand, it takes a huge amount of practice to spin a complete set on vinyl, and records are expensive, so the practicality and ease of use of digital media is always going to appeal. Then there are those artists who fall outside of what we think of as a “DJ”. These are the artists whose sets are more live production remixes, using multiple stems, loops, hardware synths, drum machines, FX, etc. But whatever the setup, whatever the technology, set in the middle of it all, will be a mixer.