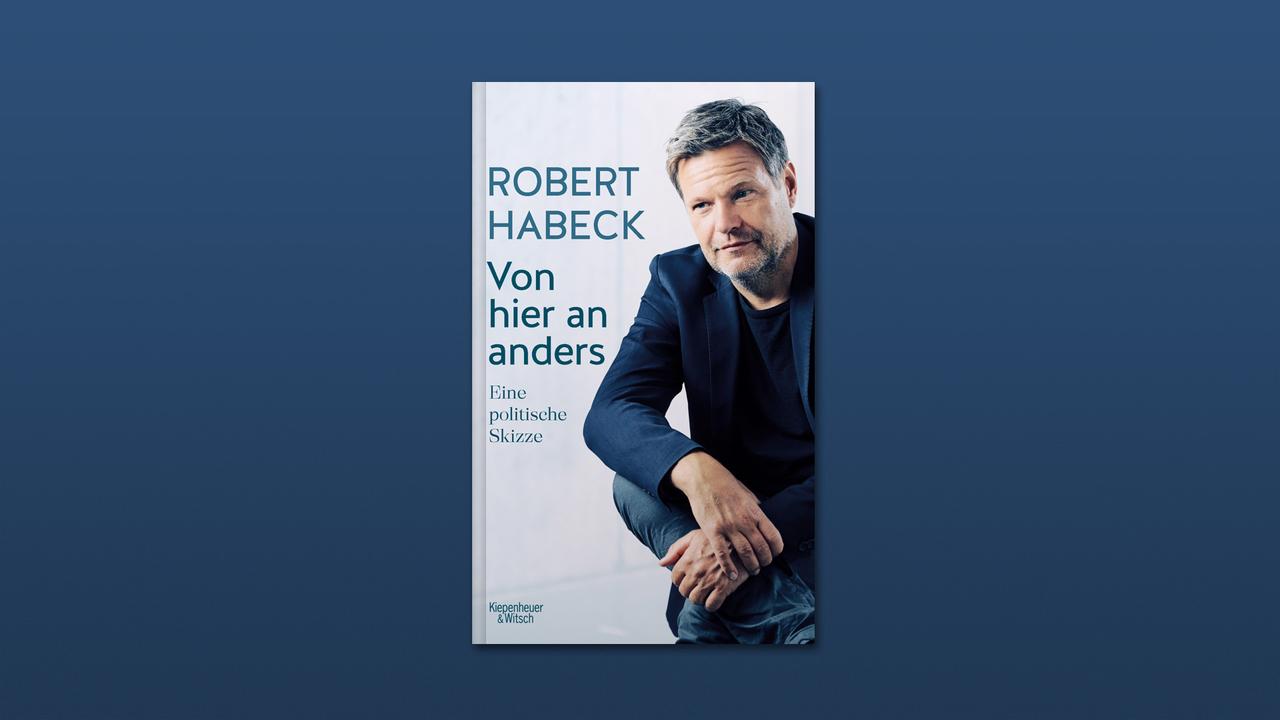

Jóhann Jóhannsson – A User’s ManualChapter 1: Englabörn (2002) - English

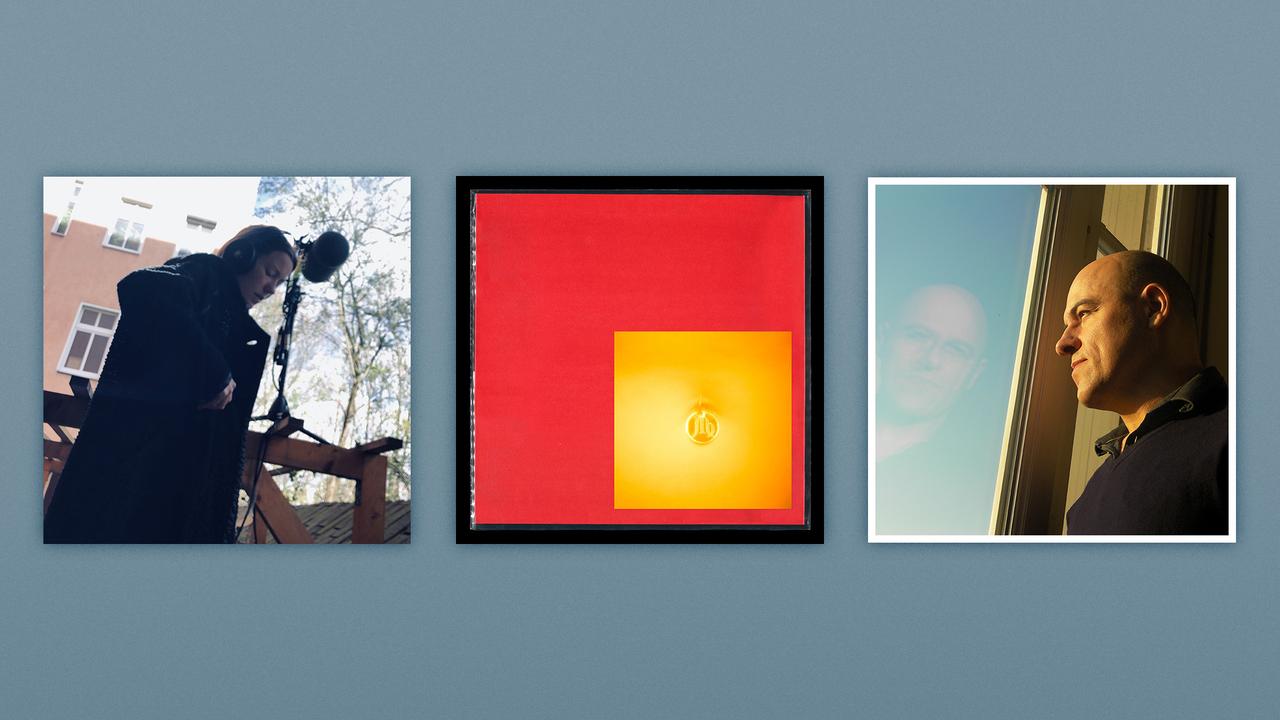

9.2.2021 • Sounds – Conversation: Kristoffer Cornils, Thaddeus Herrmann

Kristoffer Cornils and Thaddeus Herrmann have ambitious plans for the new series "Jóhann Jóhannsson – A User's Manual." Each major work by the Icelandic composer, who died in 2018, will get its own monthly review or roundtable. Twenty years after the initial release of his first solo release, "Englabörn," it's time to take a closer look at the work of the composer who made his mark on Hollywood's soundtrack industry during the last years of his career: project by project, album by album and track by track. Jóhannsson's music is one of the common musical denominators of Cornils and Herrmann. When something by him is playing, generational differences and musical backgrounds suddenly no longer play a role. Together they plunge into works that are as different as they are unifying. The motto is always: in loving memory. But the analysis, dissection and argumentative deconstruction of the albums also remain more important than ever. On the third anniversary of Jóhannsson's death, the two begin their two-year journey through the composer's back catalogue at the very beginning: after making a name for himself regionally as a member of indie bands and collectives such as Ham, Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, Ekta, Lhooq and the Apparat Organ Quartet, and as a co-founder of the collective Kitchen Motors, he debuted in 2001 as the composer of a theatre soundtrack that was subsequently reissued by the British institution Touch – and already hinted at what the Icelander would go on to accomplish throughout his career.

Deutsche Version? Hier klicken.

Thaddi: Fittingly for a debut, this album was released twice. First in 2001 in Iceland and in Iceland only: on CD-R. We still remember that medium, don't we?! Self-burned CDs for the quick and spontaneous circulation of ideas and tracks among friends. Or in this case – I'm guessing – for a precariously organised theatre production in downtown Reykjavík, where – again, I'm guessing – the aim was to sell some memorabilia to the visitors of the performances. This does not diminish the power of the composition. In 2001, Jóhann Jóhannsson was 32 years old – and laid the foundation for his career. He had previously played in several bands – and then joined the theatre. In the only interview I did with him, he said that back then he found his musical language. That applies to both "Englabörn" and "Virðulegu Forsetar," which came out in 2004. Why was that? Because he wrote for string quartet and ensembles. The play "Englabörn" – translated as "Angel's Child" – by Hávar Sigurjónsson was apparently more or less explicit, or violent. Jóhannsson contrasted the stage reality with calm, even peaceful miniatures. While I have never seen the play, the music works even without the action on stage. And of course, from today's perspective, many questions arise: The album's "hit," the opener "Odi et Amo," in which Jóhannsson's love of electronics shines through, is based on a text by Catullus, a Roman poet from the 1st century BC – "I hate and I love." That seems fitting for a piece I've never seen.

A year later, the music was reissued on Touch, the London label of Mike Harding and Jon Wozencroft. An almost obscure indie label from today's perspective, measured against the career that Jóhannsson had had until his death in 2018. However: it did and still does fit. I am forever a fan of Touch. Simply because I never know what to expect from the releases. Field recordings, noise, songs or Jóhannsson. Some of the best albums of all time were released on Touch. I wrote in above linked obituary, referring to "Englabörn," "that even today you can make the impossible possible with music.". I stand by that. From today's perspective, I also find it interesting how this album anticipated his later career in Hollywood: short pieces, always alternating: motif, development. The rest? Non-existing. Refreshing and deep. Kristoffer, we are both avowed fanboys of Jóhannsson. Do you remember when you first heard this album? I'm asking because I can't. Whether it was before "Virðulegu Forsetar" or after, I don't recall. Instead, I try to understand and analyse the discography in chronological order. During this process, a certain pattern emerges.

Kristoffer: Which one?

Thaddi: This first album hints at a compositional line of Jóahnnsson's that he has taken up again after a few years – especially in his soundtrack work in Hollywood. Short sketches, which are then explored and developed over the length of an album.

"Englabörn" is Jóhannsson in a nutshell, and that is all the more impressive because it is a debut.

Kristoffer: Agreed. The motif from "Odi et amo" runs through this album in various versions, which can also be considered an album because he reorganised the original soundtrack work. In fact, in the original track list, "Odi et amo" was at the very end, and not in this, shall we say, dub version, which closes the Touch release. And of course, certain stylistic devices that he uses here for the first time are also very present on later releases. Some, like the glockenspiel, accompanied him for not too long, others started to emerge and announce themselves. The rhythms on "Sálfræðingur" will one day lead us to "Sicario." "Englabörn" is Jóhannsson in a nutshell, and that is all the more impressive because it is a debut. By an experienced musician of course, but also by someone who was previously active in the context of others. He was a band member who here suddenly becomes a composer – and succeeds in the process. That's pretty rare. But to come back to your initial question: I don't remember when exactly I heard "Englabörn" for the first time. I can only assume that I got hold of the vinyl edition of the Touch version at the beginning of the last decade – I only came across his work quite late thanks to "The Miners' Hymns." And although I understand that this album provides the key to his later work, I essentially feel like Catullus when it comes to this record: Odi et amo.

Photo: Antje Taiga

Thaddi: Ha! I feel the same way. Though for me, it's not a conflict between hating and loving. I rather feel a certain detachment in myself regarding the record. That's not the case with "Virðulegu Forsetar." The longer I think about it, the more certain I am that I heard the latter first. That may not seem important from today's perspective, but it was totally important at the time. Because it manifested the basic tone of Jóhannsson's music, which I still appreciate today. The epochal, the dark, and yes: the pastoral. But I digress.

Kristoffer: Right up my alley, though. I think "Englabörn" and "Virðulegu Forsetar" are two sides of the same coin, because they only open up the whole cosmos of Jóhannsson's work as a composer in combination with each other. But we will deal with the second album next month. Right now, we are talking about "Englabörn," an album that, partly because of the occasion and probably because of logistical or financial restrictions, makes do with a very spartan instrumentation: a string quartet is at the centre, which basically means we are dealing with chamber music. Accordingly, it also sounds, I'm sorry, a little la-di-da. Perhaps that's where my socio-economic background comes in, but I can definitely hear a bit of bourgeois complaisance in the album. Sometimes at least. Other times, however, I live in this music, fully and completely. Those are the moments when I submerge myself in its subtleties. "Bað," for example, is a piece that has a special place in Jóhannsson's discography: the flattest possible sound ever. No reverb on the glockenspiel, no spatiality. A bittersweet miniature that sometimes makes me sick because I find it too sentimental – but which, on the other hand, I appreciate very much for its sonic radicalism. He's never sounded drier after that.

Thaddi: The "great" thing is: Apple Music shows me this piece as "Bad." Here's to international umlauts. Anyway.

Kristoffer: Not at all irrelevant, because that's actually the German translation and you would also pronounce it much like the English word "bath"! Fittingly, because it has just that weird acoustics – the kind of sound you only get in between tiled walls.

Thaddi: I sometimes think that you could consider that album to be a reaction to the Iceland hype of that time. I am neither questioning Jóhannsson's musical vision, nor do I want to re-open any long-forgotten trenches. From today's perspective, however, I sometimes think there was a guy working with a couple of violinists who simply said: "You know what? Fuck you."

Kristoffer: The nicest thing I've ever read from him was this: in an interview he was asked which interview question – meta, meta! – he could no longer stand. Why there was so much great music coming out of Iceland, he said. So it did indeed bother him. However, I personally find it rather unlikely that he tried to confront this in a commissioned work that would primarily have only been received regionally, had it not been reissued by a larger label.

Thaddi: Agreed, fair point.

Kristoffer: However, the music-historical context is important. Sigur Rós had released "Ágætis Byrjun" two years earlier, múm were doing múm things, and there were also links there. However, I don't think he wanted to distance himself from that. Just as his reinvention as a solo composer did not necessarily represent a radical break, if I may clarify what I have said earlier: Jóhannsson continued to work with many people from his immediate surroundings, just like with Hildur Guðnadóttir, who joined him a little later to work with him closely for more than a decade and a half. I also never really had the feeling that he was positioning himself against any prejudices with his music. Although, unfortunately, we now have to talk about something else: Neo-Classical music. That's a phenomenon that he's ahead of here, that he's instrumental in defining and yet, I'd say, overcoming in advance.

Thaddi: Honestly, with which album do you think he left his footprints in this "cesspool of horror?"

Kristoffer: With this one! Just compare "Ég Átti Gráa Æsku" with what Ólafur Arnalds did only a few years later on "Dyad 1909," for example. It's infinitely cornier and also much more in your face in terms of rhythm, but the basic ingredients are very similar.

Thaddi: I was never ever able to build a comparable emotional bind with Ólafur and his music. And I still ask myself: why is that? What is so special about Jóhannsson’s music? Why do I love it so much?

I think this album is saved by its sonic adventurousness on the one hand and its compositional rigour on the other.

Kristoffer: That's a question that's also on my mind and probably also the reason why we initiated this megalomaniac project, isn't it? I can't quite put my finger on it either. All I know is: in direct comparison with the subsequent Neo-Classical hype, Jóhannsson lacks that tiny bit of kitschiness that would have dragged his work – for me at least – into irrelevance. Why exactly is also something that I do not understand. Although, as I said, I hear him come very closely to it on "Englabörn." Almost, that is. And I think this album is saved by its sonic adventurousness on the one hand and its compositional rigour on the other: the sounds are exciting and fresh because he treats the source material in a quite iconoclastic way. That vocoder effect alone! On a voice reciting a Latin poem! A wonderful, double anachronism, as it were. And it is his work with exactly that melody, which is at the centre of "Odi et amo" and runs its mirror reflections through the album, that always brings me back to the beginning and whispers to me: this is not a simple tearjerker, behind it is a man with a plan!

Thaddi: Ha! I really don't want to talk about the lachrymosity of contemporary composers, but your theses are valid. Whether I share them or not: I'm not quite sure yet. For me, the vocoder is not necessarily the feature making this album so unique. I take Jóhannsson in this phase – as a late discoverer – rather personally. He played or composed something that to this day carries me away.

Kristoffer: Fair. However, I also think that without these sometimes subtle differences to Neo-Classical music as we know and define it today, it would not seem personal at all. And that's where the vocoder comes into play: Nils Frahm et al use voices rather rarely or not at all. My thesis is that this doesn't fit into their concept at all, because the music is supposed to be as universal as possible and for that it has to be – and I mean that in the most non-judgemental way possible – characterless. Music as a blank canvas onto which all emotions are to be projected. The voice doesn't fit in because it would interfere with that. But Jóhannsson amplifies the alienation effects precisely through the use of a voice and then again another time through the vocoder – a rather outdated technique in 2001, although his band Apparat Organ Quartet made extensive use of it at the same time. This creates a certain distance, which does not imply aloofness, however– but at least communicates to me that I can and must work my way to the core of the matter. For me, that's what makes it personal: that I, as a listener, somehow have to get involved. As I said before: "Englabörn" pleases me the most when I listen intently for the subtleties, the details and small breaks. It challenges me.

Thaddi: I don't hear a challenge here. But rather a point of contact for my "missionary" function as a still young-at-heart techno professional who hasn't listened to techno for a long time, but still wants to prove his own relevance and credibility or relatability.That's where Jóhannsson comes in. For example, I always like to give my uncle, who loves classical music, CDs with "Neo-Classical" stuff. It rarely works. But every now and then it does. "Englabörn" could deliver just that. Although it probably lacks the grand narrative. The tracks are simply too short. Others get to the point much more easily. I don't care, of course. I understand the highlight character of the work; the blending of and above all the reduction of different elements. Of course, the electronics, however discreet they may be, are a stumbling block. For me, it is only logical and consistent, a further development of the compositional palette.

Kristoffer: On "Englabörn" something shines through which we perhaps take very much for granted thanks to our conditioning, but which would probably irritate fans of classical music: there is a lot of manipulation, there are echoes of ambient and IDM, as heard at the turn of the millennium. Very subtle, of course, but nevertheless essential to this music. I can imagine that this does make it difficult for people attuned to classical music to properly digest "Englabörn." Other albums or soundtrack works in Jóhannsson's career are more accessible in those terms.

Thaddi: It's hard for me to judge, since for me the connections are clear and obvious – for others, they probably aren't. Ambient is a term that simply means nothing to the "old folks." IDM certainly doesn't, either. As a little missionary with a CD under my arm, I don't even open up those contexts. I just say: I've got some music that I hope you will like. No more, no less. But we're digressing again. Let's wrap this up: thumbs up or thumbs down?

Kristoffer: I told you: Odi et amo! Although, after this conversation, I tend towards the latter. It's an album I have to immerse myself in and spend a lot of time with. But when the sparks fly, I end up being consumed by flames. At this very moment I'm also overlooking the snow-covered roofs of Berlin from my window. Fits perfectly. What about you?

Thaddi: This album is important to me – even if I can't really say why. It is a fragmentary panoramic flight over a landscape or region that is as foreign to me as it is familiar. In other words: I love it – like practically everything else by Jóhann Jóhannsson. Why? This is hopefully something we'll figure out in the course of this series!